"Daddy - why are you here? I thought you were miles

away!"

"Well, I was," said Mr Rivers. "But Miss Grayling telephoned

to me to say that little Sally Hope had appendicitis and the surgeon they

usually had was ill, so could I come straight along and do the operation.

So of course I did! I hopped into the car, drove here, found everything

ready, did the little operation, and here I am! And Sally will be quite

all right and back again in school in about two weeks' time!"

. . . in the San, Sally slept . . . her pain gone . . . What a deft, quick

surgeon Darrell's father was - only thirteen minutes to do the operation!

Matron thought how lucky it was that he had been near enough to come.

(Enid Blyton, First Term at Malory Towers, Methuen & Co, 1946,

pp117, 119)

One thing which researchers need to bear in mind is that,

for disabled people, it is often impossible to separate our experiences

within the medical, social services and benefit systems (these latter are

also discussed here) from the rest of our daily lives. The combination

of our impairments and the effects of the medical![]() and administrative

and administrative![]() models of disability mean that this is inevitable. However, many people

within the disability movement would still say the fact that I am disabled

is what is relevant, rather than the nature of my impairment. But I have

included the following section for three reasons: to provide some insights

into the way in which disabled people, and disabled women in particular,

are treated by the British medical establishment (thus illustrating the

effects of the medical model of disability); to raise awareness of a potentially

disabling condition which can affect teenagers for the rest of their lives

and which is all too often overlooked or ignored by their parents, teachers

and doctors; and to provide a record of my individual experiences which

I will leave to others to analyse and to place within broader experiences

and histories of disability. What follows is a description of my personal

history of disablement within the medical system during the period covered

by my research, revealing the medical details of my impairment as I discovered

them myself.

models of disability mean that this is inevitable. However, many people

within the disability movement would still say the fact that I am disabled

is what is relevant, rather than the nature of my impairment. But I have

included the following section for three reasons: to provide some insights

into the way in which disabled people, and disabled women in particular,

are treated by the British medical establishment (thus illustrating the

effects of the medical model of disability); to raise awareness of a potentially

disabling condition which can affect teenagers for the rest of their lives

and which is all too often overlooked or ignored by their parents, teachers

and doctors; and to provide a record of my individual experiences which

I will leave to others to analyse and to place within broader experiences

and histories of disability. What follows is a description of my personal

history of disablement within the medical system during the period covered

by my research, revealing the medical details of my impairment as I discovered

them myself.

med1

I have always been disabled to some extent. I have probably

been visually impaired since birth, although this was not realised until

I was about seven or eight years old. In contrast to the 1990s, there was

very little awareness of sight problems among children in the 1960s, and

I was therefore one of only a few children in the school to wear spectacles.

At this time, spectacles were perceived purely in medical terms, so there

were only two styles available for children, neither of which had taken

aesthetic considerations into account. Wearing spectacles was a major factor

in my being bullied, and I was therefore disabled by my impairment to a

much greater extent than the many other visually impaired children within

the school whose sight remained uncorrected. The effect of the bullying

was also to make me do without spectacles wherever possible, impeding myself.

By the 1980s, though, many more people were recognised as being visually

impaired; spectacles came in a range of fashionable frames; and the disabling

factor had become negligible. The development of contact lenses also meant

that my impairment could be overcome to a much greater extent.

med2

I also suffered from a number of medical problems as a

child, which left my immune system weakened and as a teenager I suffered

from severe chicken pox followed by pneumonia and recurring chest problems,

as well as from numerous minor illnesses. I also suffered a fracture of

my right elbow following a fall at the age of fourteen, and a spontaneous

fracture of my right foot at the age of nineteen, which left both limbs

permanently weakened and put an end to my dancing career![]() .

.

med3

After beginning work as a journalist in 1984 at the age

of twenty-one, I began to suffer from severe migraines, but these were

eventually traced to an allergy to cows' milk products, and by cutting

these out of my diet the migraines ceased. (I am also allergic to eggs

and potatoes, although I enjoy sheep and goats' milk products and sweet

potatoes without any ill-effects.) Shortly after this, in autumn 1985,

after moving to the East End of London, I suffered from a chest infection

which took six months to shake off, but following this I enjoyed relatively

"good" health for four years. In September 1988, at the age of

twenty-six, I began my research into girls' school stories at the University

of East London, when I registered for a part-time M.A. by Independent Study.![]() At the same time, I continued to work as a freelance journalist

At the same time, I continued to work as a freelance journalist![]() ,

fitting in my studies around paid work. However, after I had been studying

for just over a year, in December 1989, I developed another serious chest

infection. I recovered from this in January 1990, but continued to suffer

from fatigue and minor illnesses.

,

fitting in my studies around paid work. However, after I had been studying

for just over a year, in December 1989, I developed another serious chest

infection. I recovered from this in January 1990, but continued to suffer

from fatigue and minor illnesses.

med4

Then, in May 1990, when travelling

by train to Liverpool to carry out research for the television documentary

series Breadline Britain in the 1990s![]() ,

I was gradually overcome by intense pain and muscle spasms across my chest

and upper back and down my spine, with the site of the pain appearing to

be just to the right of my spine between my shoulder blades. I also had

general weakness and pins and needles down my right side, arm and leg with

great difficulty in walking as a result of this and the intense pain, and

my neck was very stiff with limited movement, particularly to the left.

This was the onset of the impairment which caused me the greatest difficulty

during the period of my research.

,

I was gradually overcome by intense pain and muscle spasms across my chest

and upper back and down my spine, with the site of the pain appearing to

be just to the right of my spine between my shoulder blades. I also had

general weakness and pins and needles down my right side, arm and leg with

great difficulty in walking as a result of this and the intense pain, and

my neck was very stiff with limited movement, particularly to the left.

This was the onset of the impairment which caused me the greatest difficulty

during the period of my research.

med5

Initially I tried to ignore these symptoms, assuming that

I had trapped a nerve. I alighted at Lime Street station in Liverpool,

and with some difficulty carried out the interviews which I had previously

arranged. Later I did have some concerns that I was experiencing a heart

attack, since I both smoked and had a family history of heart disease![]() ,

but had no idea how to find a hospital. I therefore returned by train to

London, where I collapsed at Euston station. Eventually my partner received

my message that I was ill and collected me by car, by which time I had

decided that I had no real cause for concern, despite the intense pain

and effects on my mobility. Looking back, of course, my judgement was severely

affected by both my condition and my denial of the seriousness of the situation;

my fear of disability was shining through.

,

but had no idea how to find a hospital. I therefore returned by train to

London, where I collapsed at Euston station. Eventually my partner received

my message that I was ill and collected me by car, by which time I had

decided that I had no real cause for concern, despite the intense pain

and effects on my mobility. Looking back, of course, my judgement was severely

affected by both my condition and my denial of the seriousness of the situation;

my fear of disability was shining through.

med6

Another motivation for denying

my pain was the fact that the following day my partner and I were due to

travel to Amsterdam for a long-planned and expensive three-day holiday,

and I was very reluctant to cancel this. Believing that there was no real

cause for concern and the pain would diminish shortly, I therefore left

as arranged. Three more days of agonising pain and disability followed,

and on my return to London I went straight to the accident and emergency

department of my local hospital. By this time I had been informed by the

Amsterdam hotel's masseur that I had a mild scoliosis of the thoracic spine![]() ,

of which I had previously been unaware. However, no X-rays or other tests

were carried out, and the doctor on duty at the hospital diagnosed a pulled

muscle - although he was unable to say which one. He therefore discharged

me after prescribing three days' worth of mild pain killers, and advised

me not to rest or to take any time off work. (Standard advice for back

pain sufferers in the UK is to carry on as normal, with a warning that

rest is counter-productive.)

,

of which I had previously been unaware. However, no X-rays or other tests

were carried out, and the doctor on duty at the hospital diagnosed a pulled

muscle - although he was unable to say which one. He therefore discharged

me after prescribing three days' worth of mild pain killers, and advised

me not to rest or to take any time off work. (Standard advice for back

pain sufferers in the UK is to carry on as normal, with a warning that

rest is counter-productive.)

med7

My own denial of the seriousness of the situation had

now been supported by the medical establishment, but despite this my condition

did not improve. At this point I was not registered with a general practitioner,

since I had complained about the administration of my previous practice,

so I had no-one to whom I could turn for a second opinion. Instead I returned

to work and suffered three more weeks of intense pain and related disability,

before being advised by my employers - who were becoming increasing irritated

by the restrictions which this placed on my activities - to consult an

osteopath. I was fortunate in finding an excellent local practitioner whom

I have seen regularly ever since, and she was able to relieve the acute

pain and related muscle spasms to some extent. After lengthy questioning,

the only cause of my pain and impairment of which we could think was an

incident on the London Underground about a fortnight before my journey

to Liverpool, when I had been crushed by a crowd of drunken stockbrokers

while "strap-hanging" on the way home from work. I had also experienced

a brief faint spell during the night before the journey when the pain came

on. Later, the osteopath felt that the chest infection I had suffered from

five months beforehand was also significant.

med8

Ten weeks after the onset of pain, in August 1990, my

pain had become chronic and I became sufficiently concerned to register

with a male general practitioner. (I would have preferred to see a woman

doctor, but there was none available within the practice.) This doctor

prescribed mild painkillers and referred me back to the local hospital;

I was given an appointment to see a consultant in six months' time, which

was the earliest available. The lengthy waiting period before seeing a

specialist and the GP's lack of concern reinforced my belief that nothing

was seriously wrong, and thanks to the osteopathic treatment, and later

to the regular acupuncture and homeopathy recommended by my osteopath![]() ,

I was able to continue working and to complete my television contract in

October 1990.By this time I believed that the reason why I was still experiencing

severe pain and disability was due to the fact that I had been unable to

rest, and that a week's holiday after finishing the contract would cure

me. (This was the first point when I questioned the medical advice which

I had received at the time of the onset of pain; I now believe that rest

and immediate drug treatment and physiotherapy would have provided my best

chance of recovery.)

,

I was able to continue working and to complete my television contract in

October 1990.By this time I believed that the reason why I was still experiencing

severe pain and disability was due to the fact that I had been unable to

rest, and that a week's holiday after finishing the contract would cure

me. (This was the first point when I questioned the medical advice which

I had received at the time of the onset of pain; I now believe that rest

and immediate drug treatment and physiotherapy would have provided my best

chance of recovery.)

med9

Despite my optimism, the effort of

trying to continue as if my impairment did not exist had left me suffering

from long-term exhaustion, and a holiday followed by several weeks' rest

made little difference. In January 1991 I therefore returned to my general

practitioner to ask if he could refer me for X-rays, bring forward my hospital

appointment and prescribe adequate pain relief in the meantime, since after

seven months I was finding the severe pain very wearing. My GP replied

that he could do nothing about speeding up diagnosis or treatment, but

would in the meantime prescribe better pain relief, although he gave me

no details or advice about the medication involved.

med10

A few days later I felt most peculiar, was unable to sleep

and noticed that the pupils of my eyes were very contracted, while there

had been no effect on my pain. I therefore consulted my acupuncturist,

who confirmed that the medication, Amitriptyline, was in fact a tricyclic

anti-depressant with marked sedative effects, effective only at combatting

the physical symptoms of depression, and that I should have been warned

to avoid alcohol and driving because of the known side-effects. I was extremely

upset by this, but challenging my GP achieved nothing but the advice to

find another doctor if I was unhappy with his treatment. I believe that

the prescription reflected the common tendency within the National Health

Service to treat women as if their problems are psychological rather than

physical, and women's visits to doctors as demands for attention rather

than for treatment.![]() The long-term effects of the drug would also have effectively prevented

me from making further demands.

The long-term effects of the drug would also have effectively prevented

me from making further demands.

med11

I therefore had little choice but to wait for my hospital

appointment, which in the event was brought forward to March 1991. I saw

a male consultant, who prior to examining me locked the consulting room

door "to keep the angry husbands out", and who made a number

of inappropriate comments such as my not needing to worry, since I "had

the body of a twenty year old" (by this time Iwas twenty-nine). He

did not order any X-rays or blood tests, but diagnosed a "slipped

disc"![]() and referred me for physiotherapy. He said he would recommend a course

of exercises, but that the physiotherapists were independent and would

administer the treatment which they thought best. Following this treatment,

he told me, he would administer an anti-inflammatory injection to treat

my "slipped disc" at my next visit. I duly visited the physiotherapy

department, where I was assessed separately by two (male) senior physiotherapists

who decided that exercises would only aggravate my condition. Having tried

traction, which also aggravated my pain, they decided to use ultrasound

and referred me for physiotherapy. He said he would recommend a course

of exercises, but that the physiotherapists were independent and would

administer the treatment which they thought best. Following this treatment,

he told me, he would administer an anti-inflammatory injection to treat

my "slipped disc" at my next visit. I duly visited the physiotherapy

department, where I was assessed separately by two (male) senior physiotherapists

who decided that exercises would only aggravate my condition. Having tried

traction, which also aggravated my pain, they decided to use ultrasound![]() and TNS

and TNS![]() treatment. In all, I made eight visits to the department and this treatment

did appear to be beneficial.

treatment. In all, I made eight visits to the department and this treatment

did appear to be beneficial.

med12

However, when I returned to see the consultant at the

end of April 1991, he became very angry because I had not been given an

exercise regime by the physiotherapists, and said that he "did not

believe in" ultrasound or TNS (the fact that the hospital's administration

clearly did believe in these treatments did not appear to concern him).

I tried to tell him that I had already tried an exercise regime recommended

by my osteopath, as well as taking up Tai Chi in an effort to stop my muscles

from wasting. I had also originally trained as a dancer![]() ,

so both understood the need for and enjoyed exercise, but knew that anything

more than very gentle exercise was making my condition worse. However,

the consultant ignored what I was saying, cancelled my physiotherapy, refused

to administer the promised anti-inflammatory injection and sent me back

to the physiotherapy department for an exercise regime. This the physiotherapists

then refused to give me on the grounds that it was contra-indicated.

,

so both understood the need for and enjoyed exercise, but knew that anything

more than very gentle exercise was making my condition worse. However,

the consultant ignored what I was saying, cancelled my physiotherapy, refused

to administer the promised anti-inflammatory injection and sent me back

to the physiotherapy department for an exercise regime. This the physiotherapists

then refused to give me on the grounds that it was contra-indicated.

med13

At the following appointment I asked again to be X-rayed,

but was refused on the grounds that "nine out of ten bad backs do

not show up on an X-ray, so there is no point". The consultant then

told me that there were no medical conditions with my symptoms (I had written

down my medical history and symptoms for him before my initial appointment,

as is commonly advised); said that if I "thought about it for long

enough [I] would realise that [I] was just depressed"; and discharged

me, walking out of the room while I was still speaking. In retrospect,

I believe that this diagnosis also reflected the common tendency within

the National Health Service to treat women as if their problems are psychological

rather than physical, and women's visits to doctors as demands for attention

rather than treatment.

med14

For the next few months I struggled to uncover the psychological

problem which was causing me such great pain and impairment, since I was

not given a referral to any form of psychiatric service. Nothing obvious

came to mind, particularly given that I had already completed lengthy counselling

in the early 1980s, following the death of my father![]() .

I had tried very hard to maintain a positive mental attitude since becoming

disabled - because I thought that it was essential to a "cure"

- and believed that I had largely succeeded up until this point. Since

the career which I had envisaged had been disrupted, in January 1991 I

had decided to complete my M.A. programme of study at the University of

East London, rather than transferring my registration to PhD as originally

planned. I had also begun working as a media and communications consultant

at the Health Education Authority, since I was unable to continue with

my journalism career and television research

.

I had tried very hard to maintain a positive mental attitude since becoming

disabled - because I thought that it was essential to a "cure"

- and believed that I had largely succeeded up until this point. Since

the career which I had envisaged had been disrupted, in January 1991 I

had decided to complete my M.A. programme of study at the University of

East London, rather than transferring my registration to PhD as originally

planned. I had also begun working as a media and communications consultant

at the Health Education Authority, since I was unable to continue with

my journalism career and television research![]() .

(In the past my work had often involved travelling by public transport,

carrying a shoulder bag, camera bag and briefcase; clearly this was now

impossible.) Although I had to time my work carefully and rest a lot, both

my academic work and paid work were proceeding well, and I did not believe

that this fitted in with a diagnosis of depression. I was also aware that

if I thought about it for long enough, I would become depressed,

particularly since I was still suffering from the effects of long-term

exhaustion.

.

(In the past my work had often involved travelling by public transport,

carrying a shoulder bag, camera bag and briefcase; clearly this was now

impossible.) Although I had to time my work carefully and rest a lot, both

my academic work and paid work were proceeding well, and I did not believe

that this fitted in with a diagnosis of depression. I was also aware that

if I thought about it for long enough, I would become depressed,

particularly since I was still suffering from the effects of long-term

exhaustion.

med15

In retrospect, I am surprised that I gave any credence to the doctor's denial of my problems, since I knew perfectly well that I was suffering from genuine pain and impairment. I also knew that I was not seeking medical treatment as a means of getting attention - as a journalist, writer and politician, I was used to having a large audience, while I have disliked and avoided doctors and hospitals since being hospitalised as a young child. However, we are taught to accept a doctor's opinion as final, apparently to the extent that if a doctor denies that a physical problem exists, we believe them. Susan Sontag also points out that:

part of the denial of death in this culture is a vast

expansion of the category of illness as such.

Illness expands by means of two hypotheses. The first is that every form

of social deviation can be considered an illness . . . The second is that

every illness can be considered psychologically. Illness is interpreted

as, basically, a psychological event, and people are encouraged to believe

that they get sick because they (unconsciously) want to, and that they

can cure themselves by the mobilization of will; that they can choose not

to die of the disease. These two hypotheses are complementary. As the first

seems to relieve guilt, the second reinstates it. Psychological theories

of illness are a powerful means of placing the blame on the ill. Patients

who are instructed that they have, unwittingly, caused their disease are

also being made to feel that they have deserved it.![]()

med16

Fortunately, in January 1991 I had also begun to see a

doctor at the charitable Nature Cure Clinic in West London, on the recommendation

of a friend who is an HIV/Aids activist. Here I was receiving herbal and

homeopathic remedies, together with dietary advice. After trying this regime

for a few months and giving up smoking without noticeable improvement in

my condition, in August 1991 the doctor there questioned me again about

my medical treatment. In particular, he was concerned that no X-rays and

blood tests had been performed. He was unable to refer me for these himself

- the clinic is staffed by doctors from the private Hale Clinic who volunteer

their services - but urged me to see my general practitioner again to obtain

the appropriate referral.

med17

My GP refused, pointing out that I had already seen a

consultant and been diagnosed as suffering from depression, but the doctor

at the Nature Cure Clinic reiterated his advice and arranged for me to

have blood tests performed privately, while my osteopath arranged X-rays

at the National School of Osteopathy in Trafalgar Square. This cost me

several hundred pounds from an income which had been drastically reduced

as a result of my impairment. It also challenged my opposition to private

medical treatment, which I had previously regarded in the light of "queue-jumping"

rather than as an alternative to no treatment at all. As Lisa Cartwright

points out: "Though medicine may control the bodies and communities

it images, it also offers imaging as a class and cultural privilege."![]()

med18

In September 1991 I received the X-ray report, which noted

"degenerative changes suspicious of old, mild osteochondritis"![]() .

Neither the doctor at the Nature Cure Clinic nor my osteopath were certain

of the meaning or significance of this, but since the site of the "osteochondritis"

coincided exactly with that part of my spine which I had always identified

as the site of my problems, it seemed reasonable to assume that a link

existed. I therefore obtained a new general practitioner, this time a woman,

and asked for a referral to a different hospital for a second opinion and

for stronger painkillers in the meantime. After reading a letter from my

osteopath my new GP seemed rather alarmed, saying that "we don't do

the little bones at medical school", but was happy to make the hospital

referral. However, she refused to prescribe stronger pain relief because

of the depression diagnosis (at this point I had been in severe pain for

eighteen months). Later she prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

tablets (NSAIs) to tackle the cause of the pain, but these left me with

a range of side-effects, including very acid urine which mimicked cystitis,

constant nausea and loss of hearing. I therefore had to abandon the tablets,

after my GP told me that "there is no point in trying other types,

since they are all the same" (fortunately, this assertion eventually

proved to be false).

.

Neither the doctor at the Nature Cure Clinic nor my osteopath were certain

of the meaning or significance of this, but since the site of the "osteochondritis"

coincided exactly with that part of my spine which I had always identified

as the site of my problems, it seemed reasonable to assume that a link

existed. I therefore obtained a new general practitioner, this time a woman,

and asked for a referral to a different hospital for a second opinion and

for stronger painkillers in the meantime. After reading a letter from my

osteopath my new GP seemed rather alarmed, saying that "we don't do

the little bones at medical school", but was happy to make the hospital

referral. However, she refused to prescribe stronger pain relief because

of the depression diagnosis (at this point I had been in severe pain for

eighteen months). Later she prescribed non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

tablets (NSAIs) to tackle the cause of the pain, but these left me with

a range of side-effects, including very acid urine which mimicked cystitis,

constant nausea and loss of hearing. I therefore had to abandon the tablets,

after my GP told me that "there is no point in trying other types,

since they are all the same" (fortunately, this assertion eventually

proved to be false).

med19

In December 1991 - shortly before completing my M.A. -

I received my new hospital appointment. This was not at the Pain Clinic

to which my GP had referred me, since it had now closed due to financial

cutbacks. Instead I was transferred automatically to the Neurology department,

although I was fairly sure that I did not have a neurological problem.

Screening there later found that I had some loss of sensation in my right

side, and nerve irritation which was affecting my right arm, but this was

due to whatever was happening to my back. I was therefore referred on to

the Rheumatology department in June 1992. At this point I was also given

a blood test for cancer. I was fairly sure that I was not suffering from

cancer, since my condition had not progressed. However, I was surprised

not to receive any counselling before the test was administered, since

this is standard practice for HIV and a positive diagnosis would be equally

devastating.

med20

At the time when I was first seen by the Rheumatology

department, my medical notes (later obtained by my solicitor) show that

the original diagnosis of depression was still affecting my treatment,

in conjunction with other assumptions about my role in life as a woman

and my failure to conform. In contrast, despite pointing out to each doctor

I have seen that I am a professional whose career has been severely disrupted

by my impairment, not one mention of this has ever been made in my medical

notes, and the effect on my life has never been seen as relevant.

med21

Rather than making notes about my symptoms as I had presented

them, the rheumatology consultant wrote after my first appointment that

"I found the inter-relationship with the mother a little over-protective

for someone of her age . . ." In fact - although I had left home at

eighteen and my relationship with my mother could not be described as close

- I had taken my mother along to provide my childhood medical history and

because she has three separate nursing qualifications, together with an

Honours degree in Psychology. (I have no reason to suppose that any of

the doctors whom I have seen have qualifications in psychology or psychiatry.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the doctor found her to be "somewhat overwhelming

in terms of pressing for a diagnosis and feeling unhappy about previous

management". The notes continued: "I would be quite interested

to interview Miss [sic] Gosling's partner who is apparently now doing most

of the work at home."

med22

It is probable that my very insistence on being viewed

as a professional woman, compounded with my appearance and non-married

status, resulted in my being viewed instead as a dysfunctional woman, whose

refusal to fulfil a traditional role, to "grow up", was my real

illness. In fact, my (male) partner, who attended later appointments, took

an equal share in the housework for many years before I became disabled,

and was always the sole cook. I had no need to "play disabled"

to avoid the washing up; in any case, before I became disabled my income

was sufficient for me to pay for domestic assistance if I had wished. (What

is true is that I had internalised the responsibility for cleaning the

house personally to the extent that I was distressed for a long time after

this ceased to be possible, until the National Back Pain Association liberated

me with the slogan "a little dirt never hurt".) I do wonder,

though, whether my initial treatment would have been different if I had

originally presented myself as someone who wished to get married and to

have a baby, yet was unable to do so as long as I had back pain.

med23

Presumably contact with my partner did convince the rheumatology

consultant that I did have a genuine physical problem, since he eventually

ordered MRI scans![]() and later wrote to my original consultant that "it is difficult to

equate this [diagnosis of depression] with the fact that she has gone back

to study for a PhD and travels down to Canterbury weekly". In April

1993, three years after my problems started, I was finally told that the

scans showed a diagnosis of Scheuermann's Disease or Juvenile Kyphosis

and later wrote to my original consultant that "it is difficult to

equate this [diagnosis of depression] with the fact that she has gone back

to study for a PhD and travels down to Canterbury weekly". In April

1993, three years after my problems started, I was finally told that the

scans showed a diagnosis of Scheuermann's Disease or Juvenile Kyphosis![]() ;

the "osteochondritis" referred to on the original X-ray report

commissioned by my osteopath. In fact, according to my medical records,

this had already been deduced by the Neurology department more than a year

beforehand from the original X-rays, when they had also noted the scoliosis.

This diagnosis had not been told to me, though, since it was "probably

incidental".

;

the "osteochondritis" referred to on the original X-ray report

commissioned by my osteopath. In fact, according to my medical records,

this had already been deduced by the Neurology department more than a year

beforehand from the original X-rays, when they had also noted the scoliosis.

This diagnosis had not been told to me, though, since it was "probably

incidental".

med24

No explanation was given to me when I did eventually receive

the diagnosis, but I was able to find out more from my work as a media

consultant to the Health Education Authority. In non-medical terms, my

upper or thoracic spine is both rounded (kyphosis), giving me round shoulders

and making me appear to have poor posture, and curved to the side (scoliosis),

making my shoulders slightly crooked. As a result the inward curve of my

lower back is also exaggerated, pushing my stomach outwards and my pelvis

back. The curvature is due to the fact that the affected thoracic vertebrae

did not develop properly during adolescence and are wedge-shaped, "malformed".

In fact, the Scheuermann's Disease is clear from looking at myself in the

mirror - particularly after comparing myself with photographs from a book

on "spinal deformities" - but I had never before realised that

my body was not "normal". However, none of the doctors whom I

had seen had noticed, with more than one saying accusingly that I had "very

poor posture".

med25

There is no obvious reason why my spine developed in this

way - there appear to be various and conflicting medical explanations -

but one possible explanation is my allergy to cows' milk products. I have

been taking calcium supplements since discovering this in my early 20s,

and a bone density scan taken in the mid-1990s was normal. However, during

my teenage years I assumed that I was getting all of the calcium which

I needed from milk, and may well have been severely calcium-deficient.

I also fractured my elbow only weeks after the onset of menstruation, which

may well have put my body under severe strain when the bones were growing.

Equally, my mother was told that my brother had just escaped having spina

bifida when he was born, so there may be genetic factors involved.

med26

The diagnosis did explain various things which had occurred

during the later years of my dancing training![]() .

For example, I had been unable to flatten my lower back against the floor

when lying down, could not lift my arms over my head properly or flatten

my back when leaning forward during "centre" exercises, and my

dancing ceased to improve as time went on. However, at the time no-one

told me that my back was different from other students', although it must

have been obvious to my teachers

.

For example, I had been unable to flatten my lower back against the floor

when lying down, could not lift my arms over my head properly or flatten

my back when leaning forward during "centre" exercises, and my

dancing ceased to improve as time went on. However, at the time no-one

told me that my back was different from other students', although it must

have been obvious to my teachers![]() ,

who did not allow me to do much pointe work and who recommended that I

train as a teacher rather than a dancer. Perhaps they did not want to upset

me, but actually the explanation would have been a great comfort, since

I was as competitive as the rest and my failure as a dancer was very distressing.

,

who did not allow me to do much pointe work and who recommended that I

train as a teacher rather than a dancer. Perhaps they did not want to upset

me, but actually the explanation would have been a great comfort, since

I was as competitive as the rest and my failure as a dancer was very distressing.

med27

Another explanation which the diagnosis provided was the

reason why I had developed lower back pain when I was about fifteen, brought

on by dancing. (Significantly, my dancing teacher's first question when

I complained of it was whether it was my upper back which hurt.) From later

reading, it appears that the pain was due to the fact that the area of

the thoracic spine affected by Scheuermann's Disease is rigid rather than

flexible![]() ,

so activities such as dancing or gymnastics which require high degrees

of flexibility can put a strain on the ligaments and muscles of the lower

back as they are required to work harder

,

so activities such as dancing or gymnastics which require high degrees

of flexibility can put a strain on the ligaments and muscles of the lower

back as they are required to work harder![]() .

However, at the time my mother was unable to interest my GP in investigating.

Although my mother was sufficiently concerned to pay for me to see a consultant

privately from a very small income - another example of paying for medical

treatment being the only option, rather than merely the quickest - he only

X-rayed my lower back, which unsurprisingly showed no problems. He did

say that he was surprised that I couldn't lift my legs higher, which perhaps

should have given him a clue

.

However, at the time my mother was unable to interest my GP in investigating.

Although my mother was sufficiently concerned to pay for me to see a consultant

privately from a very small income - another example of paying for medical

treatment being the only option, rather than merely the quickest - he only

X-rayed my lower back, which unsurprisingly showed no problems. He did

say that he was surprised that I couldn't lift my legs higher, which perhaps

should have given him a clue![]() ,

but he discharged me without carrying out further investigations. As I

was discharged, my mother and I both concluded that the pain was insignificant,

again reflecting the tendency to accept a doctor's verdict over the evidence

of our own bodies.

,

but he discharged me without carrying out further investigations. As I

was discharged, my mother and I both concluded that the pain was insignificant,

again reflecting the tendency to accept a doctor's verdict over the evidence

of our own bodies.

med28

If Scheuermann's Disease had been diagnosed during adolescence,

the correct treatment appears to have been to fit me with a spinal brace

until my spine had finished growing, which could have prevented much of

the curvature from developing. (Exercise alone would have been unlikely

to help, since a rigorous ballet training did not prevent the condition

from developing.) I would also have been warned to protect my spine because

of its vulnerability to early degenerative changes: carrying a camera bag,

shoulder bag and briefcase for long distances, together with frenetic typing

in order to meet journalistic deadlines, would not have been recommended.

If I had been diagnosed and treated in adolescence I would probably not

be disabled now, given that the majority of people with mild Scheuermann's

Disease suffer few problems. For more than ten years after I gave up dancing

I had no problems with my back, and degeneration of the affected area![]() of my spine in my twenties and related chronic inflammation, rather than

the Scheuermann's Disease itself, is the cause of my impairment today.

of my spine in my twenties and related chronic inflammation, rather than

the Scheuermann's Disease itself, is the cause of my impairment today.

med29

Following the diagnosis of Scheuermann's

Disease in April 1993, I was advised that the only treatment which could

be offered to me was a course of anti-inflammatory injections, although

I was warned that these might prove to be of little benefit![]() .

The doctor who would administer these injections was, I was told, the consultant

whom I had seen originally in 1991, who also worked at the hospital which

I was now attending. I made it clear that, given my past experience, I

was unhappy about being treated by him, but was told that I must have seen

him "on one of his off-days" and that he was the only option.

Desperate to try anything to relieve my pain - I was now being prescribed

Co-Proxamol (Distalgesic) as pain relief by my GP, after confirmation from

the rheumatologist that I was not suffering from depression, but this was

of only limited benefit - I agreed to see him again.

.

The doctor who would administer these injections was, I was told, the consultant

whom I had seen originally in 1991, who also worked at the hospital which

I was now attending. I made it clear that, given my past experience, I

was unhappy about being treated by him, but was told that I must have seen

him "on one of his off-days" and that he was the only option.

Desperate to try anything to relieve my pain - I was now being prescribed

Co-Proxamol (Distalgesic) as pain relief by my GP, after confirmation from

the rheumatologist that I was not suffering from depression, but this was

of only limited benefit - I agreed to see him again.

med30

The first injection which he administered, in December

1993, was painful but appeared to be of some benefit, although I was concerned

that he did not ask to see the X-rays or scans beforehand and had clearly

not read my notes. When I arrived for the second injection, in February

1994, he rushed to administer it without speaking to me first, so I had

no opportunity to tell him about the pain which I had suffered following

the first injection. I did ask him if he had now looked at my X-rays or

scans, but was told that he was too busy and would look at them instead

during my third visit. Present in the consulting room was a man to whom

I was not introduced, but who was described upon my enquiring as a visiting

GP with an interest in sports medicine. The consultant carried on talking

to this GP, while he administered the injection in a way which was fundamentally

different to the first. He told the GP that "Sclerosin" was marvellous

stuff which you could inject into any joint without doing harm; this surprised

me as I had always understood that great care was needed with anti-inflammatory

injections since they contained steroids. However, by the time that I had

got dressed, the consultant had disappeared.

med31

Following the injection I suffered severe pain which continued

for some weeks. My osteopath was particularly concerned, since she felt

that my reactions did not correspond with an anti-inflammatory injection

although my reactions to the first injection had. On my third visit, in

March 1994, she therefore sent the consultant a letter raising these concerns,

and I also raised them with him myself. His initial response was that I

had had a "normal reaction" to an anti-inflammatory injection;

later, though, as I was undressing, he said that he liked patients to tell

him if he had "injected them in the wrong shoulder or whatever".

He then administered a third injection - still without having seen the

scans or X-rays - which I again understood to be an anti-inflammatory.

However, the consultant subsequently wrote to my

osteopath, explaining that I had been receiving "sclerosant injections

which are mainly sugar and glycerine with local anaesthetic". He advised

her to ignore my complaints of pain, stating that "a lot of the reaction

was psychological": again, I was being accused of attention-seeking

rather than having a genuine physical problem; but again, no psychiatric

help was being offered instead.

med32

I later discovered that sclerosants are used to promote

ligament growth, in order to stabilise loose or hypermobile joints or to

treat pain caused by overstretched ligaments. The part of my spine affected

by Scheuermann's Disease is already rigid, so it is hard to think of a

medical explanation for this treatment (and a search in the Royal Society

of Medicine's library also found none). In any case, it was not the treatment

for which I had been referred or consented to, and increasing an already

stiff area of my spine was likely to cause me further problems. Since,

unknown to the consultant, my osteopath operated an open records policy,

she passed me on the letter. Subsequently, with the support of the National

Union of Journalists and later the Legal Aid Board, I began legal action

for medical negligence.![]()

med33

In the two years following the injections I suffered from

two accidents related to spinal stiffness, although I had had no accidents

at all between 1990, when my impairment developed, and having the injections

in 1994. My pain also increased, and from April 1994 I began taking the

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAI) drug Naproxen twice daily, which

was effective in reducing the my pain levels without noticeable side-effects.

I discovered that I could tolerate Naproxen, unlike other NSAIs, by chance,

but I have an ongoing concern about the long-term risks of this treatment![]() .

.

med34

I never returned to the hospital where I received the

injections, but some months previously, on the advice of the charitable

Scoliosis Association, I had obtained a referral to the Royal National

Orthopaedic Hospital (RNOH). (Unfortunately, my GP forgot to include the

name of the doctor whom the society recommended in her letter, and I never

saw him). At the RNOH I was first told that the Scheuermann's Disease diagnosis

was wrong, as my spine was not severely enough affected by the osteochondritis

to meet the medical definition, then, after the doctor saw my MRI scans,

the diagnosis was confirmed. I suspect that my posture is actually very

good for someone with Scheuermann's Disease - due to my dancing

training - which masks it somewhat, and in any case the kypho-scoliosis

is itself only mild. But the incident reflects the fact that I was being

classified according to my impairment, and any deviation from their understanding

of it was a fault of mine rather than in their knowledge or approach.

med35

I was then offered a choice of immediate physiotherapy

or a referral to the hospital's Pain Clinic; I could not, I was told, have

both. Since I was told that the immediate physiotherapy would consist only

of recommending an exercise regime before discharging me, I opted for the

Pain Clinic referral. I finally saw a doctor at the Pain Clinic in June

1994, where I was recommended for inpatient treatment in their rehabilitation

unit![]() .

I was told that I would be admitted for three weeks in January 1995, which

would have been ideal timing since I would have recently completed the

PhD research and would be about to start my "writing-up" process.

However, when I wrote to the hospital in January 1995 to ask when I would

be admitted, I was told that the doctor I had seen had had no authority

to give me an admittance date, and I would have to wait for several more

months. I was later offered an admittance date on my thirty-third birthday,

2 May 1995, but my mother had already offered to pay for me to spend ten

days in Florida with her and I decided that a holiday would be of more

benefit. Perhaps this was wise, since my second admittance date, in October

1995, was cancelled by the hospital at forty-eight hours notice. In 1996,

after discussing the treatment further and discovering that, following

cutbacks, it now consisted only of concentrated exercise, I decided that

it was no longer appropriate for me.

.

I was told that I would be admitted for three weeks in January 1995, which

would have been ideal timing since I would have recently completed the

PhD research and would be about to start my "writing-up" process.

However, when I wrote to the hospital in January 1995 to ask when I would

be admitted, I was told that the doctor I had seen had had no authority

to give me an admittance date, and I would have to wait for several more

months. I was later offered an admittance date on my thirty-third birthday,

2 May 1995, but my mother had already offered to pay for me to spend ten

days in Florida with her and I decided that a holiday would be of more

benefit. Perhaps this was wise, since my second admittance date, in October

1995, was cancelled by the hospital at forty-eight hours notice. In 1996,

after discussing the treatment further and discovering that, following

cutbacks, it now consisted only of concentrated exercise, I decided that

it was no longer appropriate for me.

med36

However, the RNOH arranged instead for me to begin physiotherapy

at a local hospital in Cornwall, where I moved temporarily in January 1996.

This began promisingly enough, with two forty-minute assessment sessions

by a senior physiotherapist. Following these, she told me that my current

exercise regime already included all of the exercises which she would have

prescribed, agreed that I was not suffering pain as a result of stiffness

- since the exercises had left me relatively supple - and noted the permanent

muscle spasms around my spine. She then arranged for me to have twice-weekly

hydrotherapy sessions to build up my upper body strength, together with

ultrasound to treat the spinal inflammation. (This was almost five years

after the original ultrasound treatment was cancelled, and six years after

the onset of impairment.) Unfortunately, however, her instructions and

diagnosis were not communicated to the student physiotherapist who was

told to oversee my treatment, and she immediately started me on spinal

mobility exercises. This is the standard treatment for lower back pain;

her actions reflected the facts that the overwhelming majority of back

problems involve the lower back and that patients are defined by their

impairment rather than their individual symptoms.

med37

As I exercised, the combined effects of the buoyancy and

the hot water in the hydrotherapy pool relaxed the protective muscle spasms

around my spine, and the first session left me stiff and in increased pain.

Despite my complaints, though, the student continued the exercise regime

at the next session, and I felt unable to challenge her in case I was denied

treatment. The following morning I woke up with such stiff joints that

I fell over and fractured a toe in my left foot. This left me in increased

pain and unable to exercise or to walk more than a few yards for over a

month - although I still ran a meeting of the Chalet School girls' group![]() in London three days later - but continuing nonetheless with the (now)

correct hydrotherapy exercises did appear to be increasing my muscle strength.

However, within one week of my foot healing the hydrotherapy was abruptly

cancelled, after one member of staff was transferred to another hospital,

the student left for the Easter holidays and the senior hydrotherapist

started working part-time. At the time of writing, over twelve months after

the fall, my toe was still discoloured.

in London three days later - but continuing nonetheless with the (now)

correct hydrotherapy exercises did appear to be increasing my muscle strength.

However, within one week of my foot healing the hydrotherapy was abruptly

cancelled, after one member of staff was transferred to another hospital,

the student left for the Easter holidays and the senior hydrotherapist

started working part-time. At the time of writing, over twelve months after

the fall, my toe was still discoloured.

med38

Fortunately, as a result of the fall

I was prescribed a strong pain-killer, Zydol, by my new Cornish GP, which

was then put on a repeat prescription for me. This was the first time since

becoming disabled that I had received adequate pain relief, since even

after my depression diagnosis was discounted my London GP had refused to

prescribe anything stronger than Distalgesic on the grounds that "no

matter how small the risk, if you became addicted it would be my career

on the line". But with the Naproxen acting as an anti-inflammatory

and with analgesia in the form of Distalgesic and Zydol, I finally had

guaranteed access to effective drug treatment. I am, of course, concerned

about the long-term effects![]() ,

but if a negative choice, it was still the best choice for me.

,

but if a negative choice, it was still the best choice for me.

med39

There are many reasons for the control mechanisms operating

around pain relief, of which the fear of the patient's addiction and the

fear of the professional consequences in that event are important ones.

However, there are also issues of doubt of the patient's pain, suspicion

as to their motives, the belief that the patient should "learn to

live with it", moral objections to interfering with what is often

seen as being imposed by a divinity, and the simple enjoyment of power

over another human being. The mental distress caused by the withholding

of pain relief cannot be underestimated, and ditto the anxiety caused by

not knowing whether pain relief will be forthcoming from one appointment

to another. I believe that everyone has the right to make an informed choice

about their own drug use: they may not always be capable of judging the

effects on their life and health, and this should be monitored professionally

and concerns raised if necessary; but when fully informed, they are in

a far better position than anyone else to judge whether the benefits outweigh

the risks.

med40

Access to drug treatment did not, however, "cure"

me, neither did it negate the effects of my impairment. After more than

six years of disability, the combination of the drug treatment, complementary

therapies, changes to my lifestyle and a regime which included rest, good

nutrition and exercise did have the effect of relieving the worst of my

pain and allowing me to live my life as fully as possible. But I still

suffered from chronic and widespread pain which often made me feel very

unwell and meant that I was easily fatigued; had very limited movement

in my neck; and had problems with my right arm and leg which were exacerbated

by walking. I also continued to lack a detailed diagnosis and specialist

medical care, which medicalisation encouraged me to demand; advice from

the "medical expert" in my negligence action![]() was confusing and later proved to be false.

was confusing and later proved to be false.

med41

Then, in November 1996, I obtained a referral to a consultant

at a Spinal Disorders Unit at a private London hospital, with specialist

experience of treating Scheuermann's Disease. This referral was arranged

via a colleague with contacts in the medical profession and was possible

only because of my own professional contacts; if these contacts had not

existed, it is quite possible that I would never have seen a specialist.

After examining the MRI scans and confirming that my impairment was indeed

due to a degenerative condition arising from Scheuermann's Disease, and

exploring the other steps which I had taken to treat it, the consultant

prescribed a spinal brace for six months. Exercising the affected area

was aggravating the inflammation; immobilising my spine should help to

reduce the inflammation, and thus the pain. Underlining the links between

my experiences as a disabled researcher and my research, I was to wear

the brace until the day I was due to hand in my PhD (my "writing-up"

time had necessarily been extended due to long periods of illness in 1996).

I discuss my experiences of wearing the brace, together with my personal

experiences of disability, on my Home Page web site in My-Not-So-Secret-Life

as a Cyborg.![]()

med42

My experiences as a disabled researcher within the medical

system highlight several points. First, I was not perceived by the medical

profession as a researcher, but rather as a "defective" woman

(no doubt my sexuality also affected this attitude). As a woman I was not

supposed to carry out research or to act on equal terms with men, but to

cook and clean for my husband and to defer to my doctor. Second, the medical

profession did not assign any importance to treating me: because I was

defective, I was undeserving![]() .

Not only was I defective in terms of my femininity and sexuality, I was

also defective because I was impaired. In retrospect it is clear that the

medical profession itself had no difficulty in recognising my condition

as long term, but to tell me this would have been to admit their own limitations.

Instead, the reason why I did not get "better" was given to be

my own psychological defects. As Morris points out: "It is, of course,

less frightening for others to explain our physical differences in terms

of personality inadequacies - it is yet another way of saying that it couldn't

happen to them."

.

Not only was I defective in terms of my femininity and sexuality, I was

also defective because I was impaired. In retrospect it is clear that the

medical profession itself had no difficulty in recognising my condition

as long term, but to tell me this would have been to admit their own limitations.

Instead, the reason why I did not get "better" was given to be

my own psychological defects. As Morris points out: "It is, of course,

less frightening for others to explain our physical differences in terms

of personality inadequacies - it is yet another way of saying that it couldn't

happen to them."![]() By not investigating the nature of my impairment, it was easier to assert

the psychological cause of it. I, on the other hand, continued to believe

in the physical nature of my impairment, and in my right to equal treatment,

including a classification according to the medical model of disability.

By not investigating the nature of my impairment, it was easier to assert

the psychological cause of it. I, on the other hand, continued to believe

in the physical nature of my impairment, and in my right to equal treatment,

including a classification according to the medical model of disability.

med43

Third, the effects of medicalisation profoundly affected

my own attitude to my impairment, and thus to my whole life. For two years

I was unable to see myself as disabled, because I saw my impairment as

a medical and thus "curable" problem. At the least, I therefore

saw myself as "defective" in not being able to obtain appropriate

medical treatment. (Similarly, my mother's grief over the sudden death

of my father had been compounded by her failure to persuade a doctor that

he needed treatment.![]() )

I also did not see myself reflected in stereotypes of disabled people,

and had not yet gained access to images produced by disabled people themselves.

In addition, I did not see myself as having anything in common with the

other disabled people whom I knew, since I had a "medical" problem,

while - in contrast to popular imagery - they appeared to be strong and

in control of their lives.

)

I also did not see myself reflected in stereotypes of disabled people,

and had not yet gained access to images produced by disabled people themselves.

In addition, I did not see myself as having anything in common with the

other disabled people whom I knew, since I had a "medical" problem,

while - in contrast to popular imagery - they appeared to be strong and

in control of their lives.

med44

Morris points out that:

The experience of ageing, of being ill, of being in pain,

of physical and intellectual limitations, are all part of the experience

of living. Fear of all these things, however, means that there is little

cultural representation that creates an understanding of their subjective

reality.![]()

This was extremely isolating, since I therefore experienced my

"treatment" as being due to a personal lack rather than to disabilism.

It also prevented me from accessing the enormous amount of support and strength

which can be drawn from the disability movement. Thanks to the effects of the

disability movement on current thinking in the Labour movement, though, and

to prior contacts with Jenny Morris, Keith Armstrong and Judy Hunt, I experienced

the eventual realisation that I was disabled with huge relief, and embraced

it at once as a potentially positive identity rather than as the personal tragedy

and ultimate blow which society encourages us to believe of it.

med45

Click here to read an update of my condition seven years on.

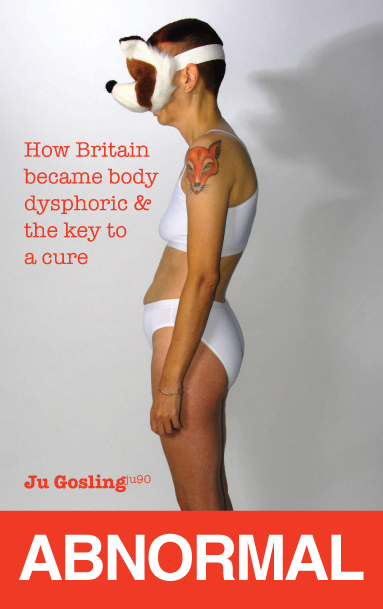

| Dr Ju Gosling aka ju90's ABNORMAL: How Britain became body dysphoric and the key to a cure is available now for just £3.09 for the Kindle or in a limited-edition hardback with full-colour art plates for £20 inc UK postage and packing. |  |