The half-term holiday had been a refreshing break to all

members of IV B, and they had much to talk about when they met again.

"I had a ripping time in the country," said Dorothy. "We

went to a meet and saw all the hounds, and afterwards we ran across some

fields and caught a glimpse of the fox. It got away, and I was rather glad."

"We went to the theatre and saw The Scarlet Pimpernel,"

said Winnie.

"And we went for a long run in the car," said Daphne. "We

went to see my uncle at Cambridge, and he took us through some of the Colleges.

Coming back we burst a tyre, and we had to stop ever so long by the roadside

before Dad could get the spare wheel fixed on."

Hetty and Tess had been hiking with their brothers, and Maud had spent

the weekend with her grandmother.

(Angela Brazil, An Exciting Term, Blackie & Son, 1936, p150)

While at primary school, my out-of-school life was integrated

with my home and school life, since I spent all of my time in my home town

and almost everyone of my age went to the same school. I also enjoyed any

opportunity to write creatively, producing poems and short stories which

owed much to the style of Enid Blyton, and writing a play which was produced

by the local Brownie Pack. However, once I reached the more academic High

School![]() this ceased, and in fact I did not begin writing outside of my academic

work again until I left University

this ceased, and in fact I did not begin writing outside of my academic

work again until I left University![]() .

Once at the High School, I also saw little of my classmates out of school,

due to a combination of my geographical isolation and my parents' low income

preventing me from travelling and participating in social events. And although

I became on good terms with the local girls with whom I travelled to school

after my first year

.

Once at the High School, I also saw little of my classmates out of school,

due to a combination of my geographical isolation and my parents' low income

preventing me from travelling and participating in social events. And although

I became on good terms with the local girls with whom I travelled to school

after my first year![]() ,

we never became close. Therefore, only very occasionally did I go cycling

or swimming with my travelling companions after school, or meet up with

a friend from dancing school or from one of the rural villages between

my home and the school. And while I was friendly with many of the girls

at the High School, they all lived too far away for me to socialise with

them outside of it, severely limiting our relationships (in any case, all

of my friends had other, closer friends). This was to become particularly

frustrating as I grew older, since the last train home from the market

town where the school was situated departed at 10pm, preventing me from

going to the cinema, discos or parties even when I had a job and could

afford these.

,

we never became close. Therefore, only very occasionally did I go cycling

or swimming with my travelling companions after school, or meet up with

a friend from dancing school or from one of the rural villages between

my home and the school. And while I was friendly with many of the girls

at the High School, they all lived too far away for me to socialise with

them outside of it, severely limiting our relationships (in any case, all

of my friends had other, closer friends). This was to become particularly

frustrating as I grew older, since the last train home from the market

town where the school was situated departed at 10pm, preventing me from

going to the cinema, discos or parties even when I had a job and could

afford these.

out1

Instead,

during the summer I spent a great deal of time on the beach

Instead,

during the summer I spent a great deal of time on the beach![]() .

Before I went to school, my mother was not employed and I literally grew

up on the beach, since my mother loved to sunbathe or to collect shells

which she would later use in craft work, and she also met with many of

her friends there. (In the early years, she probably also welcomed the

escape from my grandmother

.

Before I went to school, my mother was not employed and I literally grew

up on the beach, since my mother loved to sunbathe or to collect shells

which she would later use in craft work, and she also met with many of

her friends there. (In the early years, she probably also welcomed the

escape from my grandmother![]() .)

Like my parents' friends, we had a beach hut which provided shelter when

it rained, and so for five months or more of the year we spent most of

every free day by the sea, whatever the weather. However, books were very

much part of the experience: my mother would read to me and my sister in

the afternoons; and later on bought Ladybird primers for me to read to

myself. When I went to school, I then took out my own books from the local

library, and spent a great deal of time wrapped up in cardigans reading

on the cliffs (the shore was often wind-swept, and I felt the cold badly).

I was not particularly friendly with the other children on the beach, many

of whom were summer visitors who did not mix with children outside their

parents' social set, with the rest being primary school friends who later

rejected me for going to the "snob school"

.)

Like my parents' friends, we had a beach hut which provided shelter when

it rained, and so for five months or more of the year we spent most of

every free day by the sea, whatever the weather. However, books were very

much part of the experience: my mother would read to me and my sister in

the afternoons; and later on bought Ladybird primers for me to read to

myself. When I went to school, I then took out my own books from the local

library, and spent a great deal of time wrapped up in cardigans reading

on the cliffs (the shore was often wind-swept, and I felt the cold badly).

I was not particularly friendly with the other children on the beach, many

of whom were summer visitors who did not mix with children outside their

parents' social set, with the rest being primary school friends who later

rejected me for going to the "snob school"![]() .

.

out2

I

did, though, long for a boat - many local people sailed - eventually saving

up enough money to buy an inflatable dinghy during my last years at primary

school. This was my pride and joy for about two years, when I spent most

of the summers rowing up and down the coast, but it perished when vandals

broke into the beach hut one winter and set fire to it. I also enjoyed

surfing on a polystyrene body board and generally playing about in the

water (although I was never a particularly keen swimmer), shrimping and

scrambling on the cliffs.

I

did, though, long for a boat - many local people sailed - eventually saving

up enough money to buy an inflatable dinghy during my last years at primary

school. This was my pride and joy for about two years, when I spent most

of the summers rowing up and down the coast, but it perished when vandals

broke into the beach hut one winter and set fire to it. I also enjoyed

surfing on a polystyrene body board and generally playing about in the

water (although I was never a particularly keen swimmer), shrimping and

scrambling on the cliffs.

out3

For the rest of the year, social

activities were limited to the Girl Guides, music lessons and riding lessons.

The Girl Guides had, of course, been the most popular British girls' organisation

since they were founded at the beginning of the century and this is reflected

in many girls' school stories, including the Chalet School series; I therefore

had high expectations of them from my fictional reading. Having previously

been a "Brownie", I joined my local company during my last year

at primary school, becoming a member of the Swallow Patrol. We met once

a week in the local Red Cross hall, led by a local nurse and later by one

of the primary school teachers.

out4

I found Guides hardgoing at first, particularly when we

went away to camp for a week during the summer holiday before I went to

the High School. I was extremely homesick, having never been away from

my family before, and I was also teased mercilessly, since my mother had

insisted that I sleep on a camp bed rather than on the ground because of

my history of poor health. (The teasing may also have been related to the

fact that I was about to start at the "snob school"![]() .)

As I grew older, though, I became a competent Guide, eventually becoming

Patrol Leader of the Swallows. I enjoyed the outdoor and practical activities

on offer, and particularly looked forward to the subsequent camps, since

we had very few other holidays during my childhood. Then as now, Guides

offered girls the opportunity to participate in a wide range of activities

which are more generally limited to boys, and to explore team work and

leadership in a completely girl-centred environment with military overtones.

.)

As I grew older, though, I became a competent Guide, eventually becoming

Patrol Leader of the Swallows. I enjoyed the outdoor and practical activities

on offer, and particularly looked forward to the subsequent camps, since

we had very few other holidays during my childhood. Then as now, Guides

offered girls the opportunity to participate in a wide range of activities

which are more generally limited to boys, and to explore team work and

leadership in a completely girl-centred environment with military overtones.

out5

Eventually

I became a "Queen's Guide", which required me to pass a wide

range of tests. That I got so far in the organisation is, I think, due

to a combination of factors. First, I enjoyed the personal challenges and

the project work involved. Then my mother had always insisted that we finish

anything which we started, and to become a Queen's Guide was as far as

one could go in the organisation. Most importantly, in my early teens the

Guides filled a gap in my social life and offered me opportunities which

I was unable to find elsewhere. As soon as I had been presented with my

award, though, at the age of fifteen, I left the organisation, despite

invitations to join the Ranger Guides (a sister organisation for older

girls), to become a youth leader and to assist with the Brownies. By this

time I had other options, and had no further interest in an organisation

which was monarchist and religious in its ethos - if not necessarily in

its practice - and which, despite its benefits, failed to live up to its

fictional promise.

Eventually

I became a "Queen's Guide", which required me to pass a wide

range of tests. That I got so far in the organisation is, I think, due

to a combination of factors. First, I enjoyed the personal challenges and

the project work involved. Then my mother had always insisted that we finish

anything which we started, and to become a Queen's Guide was as far as

one could go in the organisation. Most importantly, in my early teens the

Guides filled a gap in my social life and offered me opportunities which

I was unable to find elsewhere. As soon as I had been presented with my

award, though, at the age of fifteen, I left the organisation, despite

invitations to join the Ranger Guides (a sister organisation for older

girls), to become a youth leader and to assist with the Brownies. By this

time I had other options, and had no further interest in an organisation

which was monarchist and religious in its ethos - if not necessarily in

its practice - and which, despite its benefits, failed to live up to its

fictional promise.

out6

I also began taking violin

and piano lessons when I was at primary school, since a council-administered

test pronounced me to be extremely musical (I suspect that my hearing developed

to compensate for my poor eyesight). These lessons were taught to me by

a middle-aged couple who lived in a terraced cottage close to my home,

with the husband teaching me the piano and his wife the violin. I enjoyed

the broad music curriculum at my primary school, particularly the singing,

but I had no particular talent for either the violin or the piano and was

mortified when I had to play the violin in a pupils' concert at the local

Methodist Church hall. Eventually I was glad when the long journey to and

from my High School meant that it was impossible to fit the lessons in,

and was relieved when I was finally allowed to give up learning the violin

at school too![]() .

.

out7

My riding lessons were more sporadic, but since my father

had grown up on a farm![]() and had always ridden as a child, he wanted us to have the opportunity

to learn, and found the money when he could. At one point I had a few informal

lessons in a local field, but found it difficult to control the pony. I

was a great animal lover and we kept many pets at home, but the sheer size

of the animal frightened me. After it had bolted twice as well as bitten

me, I decided to stop. Later we briefly went hacking at a proper riding

school a few miles away, which I did enjoy. However, my father was made

redundant shortly afterwards and was then unemployed for nearly a year,

and we never returned.

and had always ridden as a child, he wanted us to have the opportunity

to learn, and found the money when he could. At one point I had a few informal

lessons in a local field, but found it difficult to control the pony. I

was a great animal lover and we kept many pets at home, but the sheer size

of the animal frightened me. After it had bolted twice as well as bitten

me, I decided to stop. Later we briefly went hacking at a proper riding

school a few miles away, which I did enjoy. However, my father was made

redundant shortly afterwards and was then unemployed for nearly a year,

and we never returned.

out8

(In fact, my parents always had to struggle to pay for

our out-of-school activities, since their income was very low. My mother

ran a playgroup, while my father sold insurance

door-to-door. Insurance agents had to buy their own "round" of

customers, and due to lack of capital, my father's round consisted of the

hard-to-reach rural areas and the council housing estates with the worst

reputation. This meant that he had to travel long distances to collect

premiums, frequently needing to return to clients on Friday evenings after

they had been paid. At the beginning of my High School years he was offered

a better job with another company, but later lost it when his managing

director committed suicide and the company had to cut back on staff in

order to pay death duties. Ironically, my father went on to find a job

as a Deputy Registrar of Births, Deaths & Marriages which he still

held when he died a few years later, although this also paid badly.)

out9

Later, when I grew older, I joined the local amateur dramatic

society, which had a good reputation and took itself very seriously. Initially

I performed as a dancer when needed, but increasingly I became interested

in the production side and worked as an assistant stage manager. In this

I was following an interest which I had first gained at primary school.

A prolonged period of illness had left me out of the school play (as I

had a good memory, I usually had a leading role), and when I returned to

school I was allotted to help the stage management team. My mother did

not come to the play since I was not performing - we both viewed stage

management as very menial in the 1960s - and we were astonished later when

a friend of hers sung my praises for being so competent.

out10

During the summer the town played host to a weekly repertory

company, based at the Women's Institute hall a few hundred yards from my

home. I first attended their performances as a small child, accompanying

my "Auntie Nell"![]() who received free tickets because of providing lodgings to members of the

company. She died when I was thirteen, but later I joined the voluntary

programme- and ice cream-sellers and continued to see the performances

for free. This also stimulated my interest in production, and after I decided

against becoming a dancing teacher, I initially thought of training as

a stage manager. However, I eventually decided to aim for film and television

production - I would have liked to stage manage outdoor events and music

events, but this was unthought-of for girls in the 1970s - and to continue

my studies at university level.

who received free tickets because of providing lodgings to members of the

company. She died when I was thirteen, but later I joined the voluntary

programme- and ice cream-sellers and continued to see the performances

for free. This also stimulated my interest in production, and after I decided

against becoming a dancing teacher, I initially thought of training as

a stage manager. However, I eventually decided to aim for film and television

production - I would have liked to stage manage outdoor events and music

events, but this was unthought-of for girls in the 1970s - and to continue

my studies at university level.

out11

In the meantime, I had a succession

of more menial jobs. I had begun work as a babysitter at the age of about

thirteen, boosted by my mother's reputation as a professional child carer.

I never quite understood how being her daughter made me any more reliable

than anyone else, but I continued to be the most popular babysitter in

the area until I left home, although the pay varied enormously according

to the client. During the summer after my GCE O Levels I also worked in

the seaside town to the north of my own, an overgrown fishing village which

now attracted a large number of day trippers from the East End of London.

I was employed in a "greasy spoon" cafe on the sea front, but

given my previous incompetence in Cookery lessons![]() ,

this was not a conspicuous success. I only felt confident when I was selling

ice cream on the beach or serving chips, and was particularly nervous of

the coffee machine.

,

this was not a conspicuous success. I only felt confident when I was selling

ice cream on the beach or serving chips, and was particularly nervous of

the coffee machine.

out12

Luckily, the following year I obtained a weekend and holiday

job working in a gift shop in the same town. As well as cheap jewellery,

vases, novelties etc the shop sold an enormous range of yellow pottery

adorned with plastic pixies, inscribed with "A present from . . .

". To my astonishment this stock sold at a phenomenal rate, with whole

coach parties crowding into the shop to admire and then buy. The shop was

owned by a very pleasant middle-aged couple, members of the same amateur

dramatic society, who were extremely sympathetic when my father died within

a few weeks of my starting work there![]() .

However, I was rather taken aback when I realised that the same tea bag

was used to make all three of us the mid-morning cup of tea, after which

it was carefully dried before being re-used in the afternoon. I was sad

to leave at the end of the season, though, to work for a well-known chain

store in the market town where I went to school. This paid well, and often

provided me with employment after school as well as on Saturdays and in

the holidays, but the blue nylon uniform was an unpleasant reminder of

school and the job was both boring and tiring.

.

However, I was rather taken aback when I realised that the same tea bag

was used to make all three of us the mid-morning cup of tea, after which

it was carefully dried before being re-used in the afternoon. I was sad

to leave at the end of the season, though, to work for a well-known chain

store in the market town where I went to school. This paid well, and often

provided me with employment after school as well as on Saturdays and in

the holidays, but the blue nylon uniform was an unpleasant reminder of

school and the job was both boring and tiring.

out13

Outside

of these activities, I spent much of my time reading or walking our dog

along the sea wall which bordered the marshes to the south of my home town.

Strong currents swept along the coast, attracting fishermen to the "points"

where the seawall jutted out into the water, otherwise there was little

company beyond the cattle grazing on the marshes behind. At one time parts

of the old London Bridge was stored immediately behind the wall, broken

into numbered chunks of stone, and this did attract visitors for a while.

Aside from this it was a more popular spot at night, with the condoms which

littered the occasional "pill boxes" left over from the Second

World War reflecting the only other activity available in the town. But

I did not care for boys.

Outside

of these activities, I spent much of my time reading or walking our dog

along the sea wall which bordered the marshes to the south of my home town.

Strong currents swept along the coast, attracting fishermen to the "points"

where the seawall jutted out into the water, otherwise there was little

company beyond the cattle grazing on the marshes behind. At one time parts

of the old London Bridge was stored immediately behind the wall, broken

into numbered chunks of stone, and this did attract visitors for a while.

Aside from this it was a more popular spot at night, with the condoms which

littered the occasional "pill boxes" left over from the Second

World War reflecting the only other activity available in the town. But

I did not care for boys.

out14

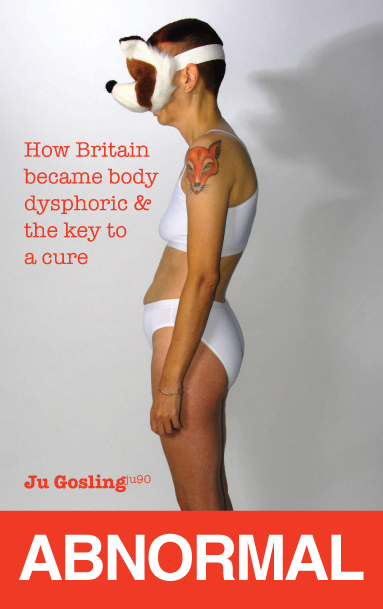

| Dr Ju Gosling aka ju90's ABNORMAL: How Britain became body dysphoric and the key to a cure is available now for just £3.09 for the Kindle or in a limited-edition hardback with full-colour art plates for £20 inc UK postage and packing. |  |