CECILY HOLDS THE FORT

by

Josephine M. Bettany

It did look nice! The only thing that would look nicer would be the title page of the printed book. Joey forgot all about history, her form, and everything else. She sat down before that wonderful machine, and when the gong rang out for Abendessen, she had her first chapter typed out.

(Elinor M. Brent-Dyer, Jo Returns to the Chalet School, Chambers, 1936, pp93-4)

When I arrived at the University of Kent at Canterbury

(UKC) in 1992, I discovered that the University placed a very high priority

on information technology (IT); in addition to a dedicated faculty, there

was a computer centre which offered all students email accounts and access

to personal computers. New students were automatically sent introductory

packs, and this meant that I quickly came into contact with faculty members,

including Wilma Strang from the Hypertext Support Unit. One of only two

similar units in the country (the other being at Oxford University), the

Hypertext Support Unit was founded to introduce hypermedia to the academic

community and to develop hypermedia teaching materials. With Wilma Strang's

assistance, I began to read theoretical work on hypermedia, most notably

by Professor George Landow of Brown University, Rhode Island (whose work

I thoroughly recommend to other researchers).![]() I also benefited from the work being carried out at UKC: for example, one

of the first and most accessible academic hypertext systems, GUIDE, was

developed at UKC by Dr Peter Brown. By 1993, I had therefore become familiar

with the concepts of hypermedia and electronic publishing. (A full introduction

to and discussion of this can be found in The E-Book & the Future

of Reading.

I also benefited from the work being carried out at UKC: for example, one

of the first and most accessible academic hypertext systems, GUIDE, was

developed at UKC by Dr Peter Brown. By 1993, I had therefore become familiar

with the concepts of hypermedia and electronic publishing. (A full introduction

to and discussion of this can be found in The E-Book & the Future

of Reading.![]() )

)

ptr1

I had written my MA thesis using an Amstrad wordprocessor,

so the final, bound version had essentially been a computer print-out.

In order to meet the criteria for examination, I had printed the thesis

on A4 paper using double-spaced text with wide margins, and the Amstrad's

dot-matrix printer![]() meant that the type was grey and not clearly defined. As a journalist,

I knew that visually the MA thesis was much harder to read than a book

or magazine. Equally, as a professional researcher and writer, and having

already produced a traditional 50,000 word thesis, I did not feel that

producing another traditional thesis provided much of a challenge for three

or four years of study. I knew that, whatever I did, I would write

my thesis using a computer. What would happen, then, if I designed it to

be read on a computer? I was already intending to record my oral

research on video, and I knew that I would have a large number of images

to include as appendices. On the computer, I could integrate all of these

with the text, creating a hypermedia thesis or hyperthesis.

meant that the type was grey and not clearly defined. As a journalist,

I knew that visually the MA thesis was much harder to read than a book

or magazine. Equally, as a professional researcher and writer, and having

already produced a traditional 50,000 word thesis, I did not feel that

producing another traditional thesis provided much of a challenge for three

or four years of study. I knew that, whatever I did, I would write

my thesis using a computer. What would happen, then, if I designed it to

be read on a computer? I was already intending to record my oral

research on video, and I knew that I would have a large number of images

to include as appendices. On the computer, I could integrate all of these

with the text, creating a hypermedia thesis or hyperthesis.

ptr2

Hypermedia is characterised by its non-linear, open-ended

structure, and conversely by its linked nature.![]() Presenting my research electronically would therefore allow for a greater

breadth of research to be presented than in a traditional linear thesis.

Feminist research is characterised by crossing borders between traditional

academic disciplines, and Communication & Image Studies is in itself

a multi-disciplinary area of study, so this seemed to be particularly appropriate

to my research field. The nature of my research, too, had already made

it inevitable that traditional academic boundaries would be broken. And

as the subject of my research was books and reading, and I was looking

in detail at the part which books played in girls' and women's lives during

the twentieth century, it seemed highly appropriate that the form and presentation

of my work should explore the future of books and reading in the twenty-first

century.

Presenting my research electronically would therefore allow for a greater

breadth of research to be presented than in a traditional linear thesis.

Feminist research is characterised by crossing borders between traditional

academic disciplines, and Communication & Image Studies is in itself

a multi-disciplinary area of study, so this seemed to be particularly appropriate

to my research field. The nature of my research, too, had already made

it inevitable that traditional academic boundaries would be broken. And

as the subject of my research was books and reading, and I was looking

in detail at the part which books played in girls' and women's lives during

the twentieth century, it seemed highly appropriate that the form and presentation

of my work should explore the future of books and reading in the twenty-first

century.

ptr3

In developing a hyperthesis, I could also realise the

theory which had been developed around hypermedia within my academic field

of Communication & Image Studies. As Landow points out: "hypertext

has the potential to serve as a laboratory for theory while theory illuminates

the design, use and cultural effects of the new electronic technologies."![]() At the time, the majority of non-fiction hypertexts which were available

were based on the encyclopaedia or "database" model

At the time, the majority of non-fiction hypertexts which were available

were based on the encyclopaedia or "database" model![]() ,

while the leading-edge work being carried out at Brown University and others

was based on the "web" model

,

while the leading-edge work being carried out at Brown University and others

was based on the "web" model![]() .

In both these cases, the concerns and interests of the reader were paramount

in deciding reading paths, reflecting theories about reader-empowerment

and non-linear narratives. In contrast, I felt that it was possible to

combine the best of both linear and non-linear structures.

.

In both these cases, the concerns and interests of the reader were paramount

in deciding reading paths, reflecting theories about reader-empowerment

and non-linear narratives. In contrast, I felt that it was possible to

combine the best of both linear and non-linear structures.

ptr4

A hypermedia thesis would not, of course, have the single

controlling line of argument which typifies the traditional, printed thesis,

but I did feel it was possible to keep sight of the fact that my research

was aimed at finding a fundamental schema of analysis. My work would therefore

represent the first attempt at creating the electronic social sciences/humanities

"textbook". The hyperthesis would then demonstrate hypermedia to readers

who had not encountered it before, and within it I would explain the design

process so that other researchers would be assisted in producing new hypermedia

texts.

ptr5

Since the form would be new to most "readers"![]() ,

I decided to include a separate, but linked, hypertext, which discussed

the impact of hypermedia on the book and the future of reading

,

I decided to include a separate, but linked, hypertext, which discussed

the impact of hypermedia on the book and the future of reading![]() .

While this writing would be appropriate to my academic discipline of Communication

& Image Studies, it would also have a direct connection with my research

into the part which books play in their readers' lives. In general, the

decision to present my thesis as a hyperthesis allowed me to present other

texts alongside the core thesis on girls' school stories, underlining the

fact that a hypertext is a collection of related texts rather than a single

narrative. Whereas in a traditional thesis these other texts might have

been given the status of appendices, in the hyperthesis they "gained an

importance" which they would not have had before, since "in hypertext,

the main text is that which one is presently reading"

.

While this writing would be appropriate to my academic discipline of Communication

& Image Studies, it would also have a direct connection with my research

into the part which books play in their readers' lives. In general, the

decision to present my thesis as a hyperthesis allowed me to present other

texts alongside the core thesis on girls' school stories, underlining the

fact that a hypertext is a collection of related texts rather than a single

narrative. Whereas in a traditional thesis these other texts might have

been given the status of appendices, in the hyperthesis they "gained an

importance" which they would not have had before, since "in hypertext,

the main text is that which one is presently reading"![]() .

However, since the "appendices" all had separate narrative focuses to the

main thesis, I decided that it was more appropriate to describe the work

as a "hypertext cluster" rather than a single hypertext. While the "main"

thesis represented the culmination of my research findings, the "appendices"

represented work which I had carried out during the period of my research.

.

However, since the "appendices" all had separate narrative focuses to the

main thesis, I decided that it was more appropriate to describe the work

as a "hypertext cluster" rather than a single hypertext. While the "main"

thesis represented the culmination of my research findings, the "appendices"

represented work which I had carried out during the period of my research.

ptr6

One important element which the structure of the hyperthesis

allowed me to include was autobiographical. First, I could introduce my

personal history of reading within the Foreword![]() .

Reinharz points out that:

.

Reinharz points out that:

I also decided to include a collection of texts within

an autobiographical lexia, About the Author![]() .

Liz Stanley and Sue Wise define two principles of feminist research as

being situated "in emotion as a research experience" and "in the intellectual

autobiography of researchers". They add that:

.

Liz Stanley and Sue Wise define two principles of feminist research as

being situated "in emotion as a research experience" and "in the intellectual

autobiography of researchers". They add that:

Similarly, Reinharz points out that feminist research

is characterised by the belief that it is important to provide information

about the background and experiences of the researcher. "Some feminist

social researchers have written full autobiographies, or have written full

reports about their experiences as researchers of women . . . more commonly

the researcher adds a preface or postscript that contains an explanation

of her relation to the subject matter at hand."![]() Including an autobiographical lexia would also encourage readers to speculate

on the place of their own autobiography in structuring their responses

to popular culture.

Including an autobiographical lexia would also encourage readers to speculate

on the place of their own autobiography in structuring their responses

to popular culture.

ptr9

I decided to provide brief details about my professional

background in the shape of a CV![]() .

I also decided to include a much longer piece of writing about my own experiences

at a girls' selective state school in the 1970s, which became the linked

hypertext My Own Schooldays

.

I also decided to include a much longer piece of writing about my own experiences

at a girls' selective state school in the 1970s, which became the linked

hypertext My Own Schooldays![]() .

I wrote this partly in order to provide further autobiographical evidence,

and partly because no published accounts existed of similar experiences,

and I believed that it would be important to consider the differences between

real and fictional school experiences elsewhere in the hyperthesis

.

I wrote this partly in order to provide further autobiographical evidence,

and partly because no published accounts existed of similar experiences,

and I believed that it would be important to consider the differences between

real and fictional school experiences elsewhere in the hyperthesis![]() .

Maggie Humm points out that: "One hallmark of contemporary feminist research

in any field is the investigator's continual testing of the plausibility

of the work against her own experience"

.

Maggie Humm points out that: "One hallmark of contemporary feminist research

in any field is the investigator's continual testing of the plausibility

of the work against her own experience"![]() ,

while Reinharz states that:

,

while Reinharz states that:

Many feminist researchers describe how their projects

stem from, and are part of, their own lives . . .![]()

Later, I also decided to include a separate, but linked

hypertext which discussed my experiences as a disabled researcher.![]() Although this was not directly relevant to my research topic, it was

directly relevant to my experience of carrying out the research, and therefore

as a feminist researcher I felt that it was important to include it. Reinharz

points out that: "Many feminist ethnographers have eliminated the distinction

between the researcher and the researched and have studied their own experience."

Although this was not directly relevant to my research topic, it was

directly relevant to my experience of carrying out the research, and therefore

as a feminist researcher I felt that it was important to include it. Reinharz

points out that: "Many feminist ethnographers have eliminated the distinction

between the researcher and the researched and have studied their own experience."![]() .

She adds that:

.

She adds that:

Another reason for including my experiences as a disabled researcher was the fact that it allowed me to address ongoing debates about the body within my academic field of Communication & Image Studies which were not directly relevant to girls' school stories. And the fact that disability has had such a low profile within the academy in the past provided further justification from a feminist research perspective. As Reinharz points out:

(Discussing my personal experience of the research was an approach which I would also adopt throughout the hyperthesis where relevant. Reinharz points out that:

. . . the feminist researcher is likely to describe the actual research process as a lived experience, and she is likely to reflect on what she learned in the process. I believe in the value of this approach . . .

Feminist research then reads as partly informal, engagingly

personal, and even confessional.![]()

I also decided to include part of the text of my

MA thesis![]() within the hypertext cluster, since the MA represented the first stage

of my research and only five bound copies exist. (Initially there were

four, but I had an additional copy produced when it became obvious that

many collectors wished to borrow and read it.)

within the hypertext cluster, since the MA represented the first stage

of my research and only five bound copies exist. (Initially there were

four, but I had an additional copy produced when it became obvious that

many collectors wished to borrow and read it.)

ptr14

As the presentation of my findings in a hyperthesis marked

a new stage in the development of the book and in the presentation of academic

research, and as research had not been previously carried out into reading

experiences associated with girls' school stories, I had to develop new

ways of working and to use new research techniques. This included the use

of digital video editing, desk-top publishing and multimedia authoring

software. After completing this research, I decided to include a separate,

but linked hypertext containing the information which I had discovered

about health and safety practices when working with new technology![]() .

I decided to include it first because of its relevance to the practice

of reading Virtual Worlds of Girls, and second because of the widespread

ignorance which currently exists about the safe use of computers. This

hypertext has already been published in print form by Skillset, the training

body for the film and television industry, as Health and Safety in the

Non-Linear Environment (1995).

.

I decided to include it first because of its relevance to the practice

of reading Virtual Worlds of Girls, and second because of the widespread

ignorance which currently exists about the safe use of computers. This

hypertext has already been published in print form by Skillset, the training

body for the film and television industry, as Health and Safety in the

Non-Linear Environment (1995).

ptr15

Other linked texts within the hypertext cluster include the "notes" to the "main" texts. While some are simply references or short quotes or notes, as with traditional foot- or endnotes, others include extended quotes or detailed discussions of lateral issues. Landow points out that, in printed books:

. . . One experiences hypertext annotation of a text very differently.

. . . In hypertext, the main text is that which one is

presently reading . . . any attached text gains an importance it might

not have had before.![]()

One aspect of research which hypermedia makes explicit

is the fact that no piece of research exists in a vacuum; it is all inter-connected.

In an electronic medium, these connections can potentially be made explicit

by creating links between texts. Many of the "notes" within the hyperthesis

are in fact potential links, whether they simply supply a reference or

include an extended quote. Conversely, when texts can be linked, there

is no need to summarise another piece of research unless it is directly

relevant to the topic under discussion.

ptr17

Ultimately, I also wanted to include the presentation

of my video material, The Chalet School Revisited, as a separate

lexia, having discussed the making of it within Exploring the World

of Girls' School Stories![]() .

In addition to this being an integral part of the hyperthesis, when viewed

on computer, readers/viewers could selectively view individual scenes or

tracks and decide the order in which they were played.

.

In addition to this being an integral part of the hyperthesis, when viewed

on computer, readers/viewers could selectively view individual scenes or

tracks and decide the order in which they were played.

ptr18

I could, of course, have also included my research notes

and records within the hyperthesis, but I decided that this was inappropriate.

However, I did resolve to archive all of the material, and in the future

to make it available to scholars on request where possible. I also finally

decided against including sections which merely provided a historical record

- for example, excerpts from fanzines; details of ephemera which had been

produced by the fans; and fanclub histories - and which should in any case

be kept separate from interpretation of these phenomena. This was not because

these records were irrelevant, but because by 1996 the fans themselves

were now capable of producing and publishing their own records, both in

print and electronically.

ptr19

Developing the hypertext cluster meant that I was now

effectively presenting two theses: one which presented research on girls'

school stories and their readers, including the memoir of my own schooldays

which could be compared to the educational experiences represented within

the genre; and one which was concerned with the research process itself,

including Exploring the World of Girls School Stories, The Ebook

& the Future of Reading, autobiographical details, My Experiences

as a Disabled Researcher, and Health & Safety in the Non-Linear

Environment. In the first thesis, my research into the genre of girls'

school stories was the subject; in the second, my research was the example

which illustrated the process itself, including the development of a new

means of presenting research.

ptr20

Structurally, I found that there were two challenges when

writing the hyperthesis. First, while it would be quite possible to divide

the text into virtual "pages" which could be turned, there was no point,

since it would hamper the reading process, and in any case, pages generally

create artificial divisions in the text which were not intended by the

author (an exception to this are spreads of illustrated pages). I also

considered it better to create one larger file size which contained a chapter

or lexia than a group of smaller ones which each contained a page, given

that on the World Wide Web the reader is forced to wait each time they

access a new file. However, the use of paragraphs marks divisions in the

text which are intended by the author, so explicitly dividing the

text into paragraphs rather than pages seemed to be a more "writerly" way

of doing things. In order for the reader to be able to reference the work,

I included a reference number at the end of each paragraph to replace the

traditional page-numbering system.

ptr21

The second challenge which I encountered when writing

up the research was that the ability to break down text into small self-contained

chunks meant the text as a whole lacked coherence at first draft stage.

At second draft stage, I therefore reassembled many of these chunks into

longer, more linear pieces of writing. I am, however, convinced that with

a complex piece of work such as this, with non-linear reading paths, the

author does benefit from going through this process and examining the many

different relationships which exist between chunks, before deciding how

to structure the final work.

ptr22

Equally, at the time of writing (1997), most readers had

only encountered hypermedia in the form of World Wide Web pages where text

chunks are designed to be as brief as possible, so it was important to

consider how best to reconcile the expectations of experienced Web users

and those of print readers. At the same time it was important to bear in

mind that the Web is an experimental means of communication which had far

exceeded the expectations of its designers, and to see current developments

in hypermedia as representing a transitory rather than final stage in the

(multi) medium. I therefore gave greater weight to theoretical considerations

than to contemporary examples when designing the final structure.

ptr23

At the point when I developed the idea of creating the

hyperthesis (1993), I decided that I would not concern myself too greatly

with how I would produce or "author" it. If I made initial choices

about which software![]() I would use, my design would be constrained by its limitations. It would

be better to decide on the design now, and then to choose the most suitable

software available when I came to author it, modifying the design at this

point to take account of the chosen software's characteristics and limitations.

In any case, with new software constantly being developed, it was likely

that the software which I would eventually choose had not at this point

been released to the public. Landow later described this to me as "designing

ahead of the curve", which he personally recommends.

I would use, my design would be constrained by its limitations. It would

be better to decide on the design now, and then to choose the most suitable

software available when I came to author it, modifying the design at this

point to take account of the chosen software's characteristics and limitations.

In any case, with new software constantly being developed, it was likely

that the software which I would eventually choose had not at this point

been released to the public. Landow later described this to me as "designing

ahead of the curve", which he personally recommends.

ptr24

At this point, too, the World Wide Web was in the process

of development![]() ,

and writers were using a variety of programmes, such as Guide and StorySpace,

to author their hypertexts. These programmes produced hypertexts which

were, on the whole, inaccessible to people who were not already familiar

with computing conventions, and which could only be used by people using

the same software and system as the writer. And while copies of these hypertexts

could often be obtained via the Internet, they could not be read online.

I therefore conceived the hyperthesis originally as a standalone programme

- one which did not require the authoring software to read it - and with

a custom-designed interface.

,

and writers were using a variety of programmes, such as Guide and StorySpace,

to author their hypertexts. These programmes produced hypertexts which

were, on the whole, inaccessible to people who were not already familiar

with computing conventions, and which could only be used by people using

the same software and system as the writer. And while copies of these hypertexts

could often be obtained via the Internet, they could not be read online.

I therefore conceived the hyperthesis originally as a standalone programme

- one which did not require the authoring software to read it - and with

a custom-designed interface.![]()

ptr25

At the time when I began writing up my research, I had

already created the Bettany Press![]() publications in QuarkXPress 3.31

publications in QuarkXPress 3.31![]() .

I was also aware that a multimedia XTension to the forthcoming QuarkXPress

3.32, Orion (since retitled Immedia), was in development. Corporate literature

distributed at the 1995 Apple Expo (held in December at the Olympia exhibition

centre in West London) promised that Immedia would combine sound, still

images and moving images with text, be "easy to use", be a "multiplatform

solution" (since the products created could be viewed either on an Apple

Mac or a IBM PC running Windows) and that products created with it could

be viewed over the Internet. I therefore decided to use QuarkXPress 3.32

to write up my research, since the documents could always be translated

into another format if I changed my plans.

.

I was also aware that a multimedia XTension to the forthcoming QuarkXPress

3.32, Orion (since retitled Immedia), was in development. Corporate literature

distributed at the 1995 Apple Expo (held in December at the Olympia exhibition

centre in West London) promised that Immedia would combine sound, still

images and moving images with text, be "easy to use", be a "multiplatform

solution" (since the products created could be viewed either on an Apple

Mac or a IBM PC running Windows) and that products created with it could

be viewed over the Internet. I therefore decided to use QuarkXPress 3.32

to write up my research, since the documents could always be translated

into another format if I changed my plans.

ptr26

In the event, by 1996 the success of the World Wide Web

meant that my aims would be better fulfilled by presenting the hyperthesis

as a web site, which could be read in whatever browser (Netscape, Internet

Explorer etc) the reader was familiar with. I therefore translated the

documents back into Microsoft Word and then saved them in RTF (Rich Text

Format) before translating them into HTML using the shareware programme

TextToHTML 1.3.4. I then began to author the hyperthesis using Netscape

Navigator Gold as the main editing programme, with Microsoft Word for editing

the code where necessary.

ptr27

Bob Cotton and Richard Oliver set out four main principles for creating hypermedia products:

Returning to Cotton and Oliver's first point, the utilisation

of different media to do what it does best, I wanted to use images to "show"

rather than simply to "tell" the reader where this was relevant. This seemed

to me to be more in keeping with the empowering and open nature of hypermedia

than using a description which the reader has no choice but to accept;

it also seemed more in keeping with feminist research methodology. I had

of course, used video to record the Elinor M. Brent-Dyer centenary events,

and had edited this into the 60-minute film The Chalet School Revisited

(I discuss the presentation of the video material elsewhere![]() ).

I had structured the film so that, like the printed text, it could be broken

down into chunks, in this case scenes. When viewed on computer, readers/viewers

could selectively view individual scenes or tracks, and decide the order

in which they were played. However, in 1997 the majority of computer users

did not have access to the necessary equipment to play full-screen video,

so for the time being I had to present the film separately on tape, with

links within the hyperthesis made instead to the script.

).

I had structured the film so that, like the printed text, it could be broken

down into chunks, in this case scenes. When viewed on computer, readers/viewers

could selectively view individual scenes or tracks, and decide the order

in which they were played. However, in 1997 the majority of computer users

did not have access to the necessary equipment to play full-screen video,

so for the time being I had to present the film separately on tape, with

links within the hyperthesis made instead to the script.

ptr29

However, I was aware that the facility to compress and

store large files of moving images would soon be available, and that this

would raise ethical as well as structural questions for future researchers.

Theoretically, with enough storage space, I could have made my original

footage (the "raw" footage) available alongside my own edited presentation

of the material. Readers/viewers could then have chosen what to view and

in what order, and to see footage which I had excluded during the editing

process. They could also - if I desired - have the ability to edit their

own presentations of the material. This would have shifted the balance

of power almost completely from myself as an author/editor to the reader/viewer/editor,

although I would still, as the photographer, have determined what material

existed in the first place. But while the described potential loss of power

from the author/editor to the reader/viewer/editor is to be welcomed, what

effect would this have on the research subjects?

ptr30

To some extent, those being filmed for my research were

aware of the final form in which this footage would result; they were aware

of my motives for filming them and agreed to be filmed on this basis. Although

they had little power over the final result, they could make their initial

decision to participate by making judgements about the author/editor/researcher

and could continue to participate on this basis. But if I included the

raw footage, the subjects would lose even more power over the destination

of their images. I would therefore have decided against including it even

if it had been technically possible. Nonetheless, I could use still images

from the video material to illustrate the text, along with relevant photographs.

Throughout my research, I had taken photographs using a 35mm SLR camera,

in this case a 1987 Nikon F-401, generally shooting on 400 ASA transparency

film.

ptr31

(In fact, a compact 35mm camera would have sufficed in

most situations. I would not, however, recommend using a digital camera

at the time of writing, although transferring images to a digital medium

is obviously a much simpler process than with conventional film. But while

digital cameras are extremely light and easy-to-use, the majority can store

less than a hundred images at a time, leading to over-selection at the

point of photographing. In addition, the image quality is often only suitable

for viewing onscreen, and even when this is the primary purpose of the

pictures, it may well be that further, print uses are also found for them.)

ptr32

Cotton and Oliver point out that:

In terms of colour, I decided to retain the traditional

black of printed text for the body of the text, partly for ease of reading,

and partly to continue the association with print book design. For the

same reason, I decided to keep the background to the text or "page" white,

although I selected a "chalk" pattern to give it more texture as well as

creating an association with the traditional school blackboard. I then

decided to use blue (1919FF) for the headings and sub-headings, and red

(FF1C1E) for the paragraph numbers. These were colours which were already

associated with the research, as I had designed the associated Bettany

Press print publications using red for the background of the cover of The

Chalet School Revisited and gentian blue for Visitors for the Chalet

School. I had chosen these because red and blue were used on the "boards"

of pre-War first editions of the early Chalet School books, while gentian

blue was also the colour of the uniforms in the "Swiss" part of the series.

Blue was also reminiscent of school ink, and red of the ink which teachers

use to mark work.

ptr34

Type sizes are only relative in HTML, so I used -2 for the paragraph numbers, +1 for the body type, +2 for the sub-headings and +3 for section headings. However, I decided to create the main headings as image files, in order to be able to select the typeface which was used for them. Bob Cotton and Richard Oliver point out that:

Clearly it was important that readers could easily understand how to read the hyperthesis, and this meant that the interface design was crucial. Cotton and Oliver explain interfacing as "being able to control machines by communicating with them, and receiving feedback from them. Watching the speedo on a car dashboard and easing up on the throttle, or choosing the correct washing machine programme, are good examples". They go on to point out that:

In terms of structure, Cotton and Oliver warn that:

However, Cotton and Oliver also point out that:

I decided against including the index itself permanently

onscreen in a "frame", though, as so many Web users seem to dislike this

design feature, and also against using "buttons" as links, since these

are slow to load and add nothing to the reader's understanding. Instead

I decided to include links back to the sub- and main indexes at the end

of each lexia after a link to the next lexia in the recommended reading

path. In terms of the appearance of the links, I decided against using

the traditional underlined blue "hotwords", partly because they are visually

so distracting, and partly because I wanted the reader to be able to distinguish

between different types of links when deciding whether or not to follow

them. I therefore chose to use images instead, in the form of differently

coloured and directional arrows. I decided not to include textual alternatives

to these, thus preventing readers from using text-only browsers, because

I felt that the design was integral to the presentation. I would, however,

include this feature in an adapted version for disabled readers, which

would also be suitable for a touch-sensitive screen.

ptr39

I decided to use a black arrow![]() pointing right (in design terms, this means "next" in cultures which read

from left to right) to indicate a link to another part of the same lexia;

a red arrow

pointing right (in design terms, this means "next" in cultures which read

from left to right) to indicate a link to another part of the same lexia;

a red arrow![]() pointing

right to indicate a link to another lexia in the Virtual Worlds of Girls

hypertext cluster; and a blue arrow

pointing

right to indicate a link to another lexia in the Virtual Worlds of Girls

hypertext cluster; and a blue arrow![]() pointing right to indicate a link to a reference, used smaller than the

actual size to underline the fact that in a true hypertext, the reader

would be able to move instead to the actual text. I then used a purple

arrow

pointing right to indicate a link to a reference, used smaller than the

actual size to underline the fact that in a true hypertext, the reader

would be able to move instead to the actual text. I then used a purple

arrow![]() pointing downwards

(to show that another "level" of information was available "below" the

lexia being read) to indicate that a linked note/further information on

the topic was available, with a green arrow

pointing downwards

(to show that another "level" of information was available "below" the

lexia being read) to indicate that a linked note/further information on

the topic was available, with a green arrow![]() pointing downwards to indicate that a linked picture was available. I chose

these colours because they were the Suffragette colours, as well as having

queer connotations, and are also two of my personal favourites.

pointing downwards to indicate that a linked picture was available. I chose

these colours because they were the Suffragette colours, as well as having

queer connotations, and are also two of my personal favourites.

ptr40

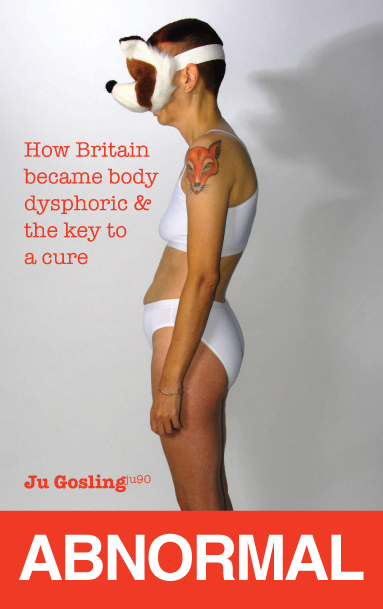

| Dr Ju Gosling aka ju90's ABNORMAL: How Britain became body dysphoric and the key to a cure is available now for just £3.09 for the Kindle or in a limited-edition hardback with full-colour art plates for £20 inc UK postage and packing. |  |